Today’s post comes from Christian Therrien, past Northwest Zone senior assistant ecologist.

Most agree all dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago.

However, looking into species found in parks reveals that some dinosaurs have indeed persisted and can be seen today!

From the Snapping Turtle to the Silver Lamprey, remnants from this forgotten time are prominent today in Ontario Parks.

However of all the dinosaurs in our parks, the most impressive is the Lake Sturgeon.

Despite surviving four mass extinction events through history and the likes of asteroids, climate change, and global volcanic eruptions that wiped out most of the earth’s species, sturgeon have not been invulnerable to man.

They are now considered a species at risk in Ontario.

A remnant from 400 million years ago

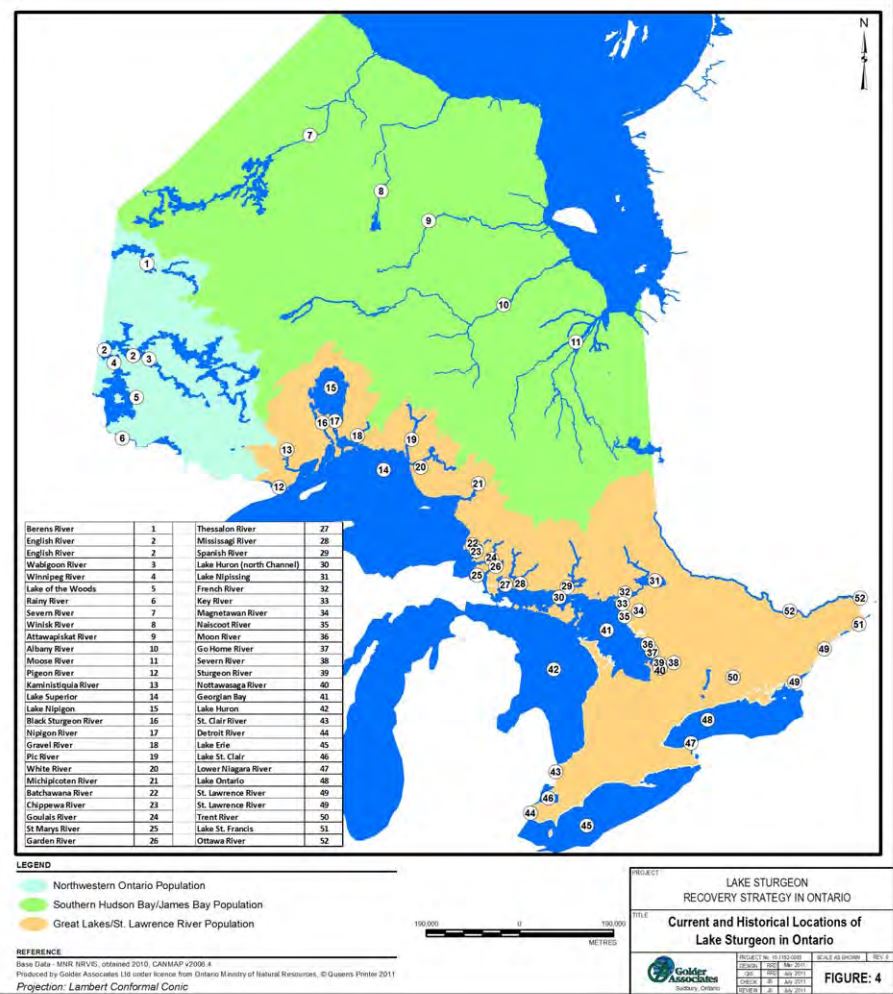

Lake Sturgeon inhabit large lakes and rivers throughout most of Ontario and are found in several provincial parks, including:

- Kakabeka Falls Provincial Park

- Pigeon River Provincial Park

- French River Provincial Park

- Missinaibi Provincial Park

- Batchawana Bay Provincial Park

They are a living fossil whose body shape and morphology has been around for millions of years!

Lake Sturgeon, like all sturgeon, retained its skeleton made of cartilage (not bone!) and shark-like caudal fin that first appeared on its ancestors 419 to 359 million years ago.

Since then, they’ve changed ever-so-slightly.

Sturgeons as we might recognize them today began to appear in the fossil record some 174 to 201 million years ago and have been nearly indistinguishable from sturgeon today since 100 to 94 million years ago.

Their persistence today can be explained by their life history strategies.

Lake Sturgeon get to tremendous sizes (the Ontario record is over six feet!) and can live for well over 100 years. In fact, a 208 lb Lake Sturgeon caught in Lake of the Woods in 1953 was 154 years of age!

In addition to the ability to grow large, sturgeon have a thick suit of bony armour called scutes, making them a tough meal for any predator.

All this, paired with the fact they feed on invertebrates, small insects, and other plentiful organisms that live on the bottom of our waterways, has allowed them to persist in this form for millions of years.

From nuisance to caviar

Unfortunately, even their large size and thick coat of armour could not defend them from the threats causing their decline.

Lake Sturgeon were first scorned by early settlers for their ability to destroy fishing gear and were culled as a nuisance species.

Commercial markets began to pop up throughout Ontario for smoked, dried, and fresh sturgeon meat and caviar after 1860, peaking by 1900.

In addition to food, sturgeon were a source of oil, leather, and isinglass, a product used in beer and wine making.

The commercial harvest was the most significant contributor to population collapse by the 1920s, while additional factors such as pollution, the creation of dams blocking access to spawning grounds, and invasive species present ongoing threats to Lake Sturgeon.

This serves in contrast to the Indigenous peoples of Ontario who hold these fish in high regard.

Elders report that sturgeon are used as a food source, scrapers are made from the scutes, arrowheads from the tail bones, and containers from their skin.

Sturgeon also play an important part in spirituality.

Today Lake Sturgeon are considered a species at risk in Ontario

The Ontario Great Lakes – Upper St. Lawrence populations are listed as endangered, the Saskatchewan – Nelson River populations are listed as threatened, and the Southern Hudson Bay – James Bay populations are listed as special concern.

As endangered and threatened species, the Lake Sturgeon of the Great Lakes – Upper St. Lawrence and Saskatchewan – Nelson River populations are protected under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA).

These populations also receive habitat protection and a Recovery Strategy has been published which provides scientific advice on actions that should be taken to help recover Lake Sturgeon in Ontario.

Population monitoring is also done on all three populations.

For information on fishing for Lake Sturgeon, check out the Ontario Fishing Regulations.

Research is ongoing by the Province of Ontario on all populations of Lake Sturgeon to identify and assess migration barriers, improve water management at hydrological dams, assess subpopulations whose population sizes and trends are unknown, and determine the effects of invasive species on Sturgeon.

Research continues at Kakabeka Falls to assess Lake Sturgeon spawning success.

A walk through Jurassic Park

For modern day dino hunters, you may still be able to catch a glimpse of this Ontario dinosaur.

Lake Sturgeon can sometimes be seen during late spring spawning at the base of rapids, dams, or waterfalls.

Kakabeka Falls Provincial Park is a great place to view sturgeon spawning. Safely watch sturgeon from the park’s viewing platform high above the Kaministiquia River.

Next time you’re on a river walk or taking a dip in the many lakes in Ontario, think about the gentle giants that persevered for millions of years but today need our help to survive.

Respect waterways by keeping them litter-free, don’t leave behind any fishing lines, and clean your equipment between uses.

Keep your eyes open, you never know what you might see on your next park adventure.

If you’re lucky, it might be a dinosaur.

This is the sixth edition of our 2023 species at risk series.

Read our previous edition: A ghost in the attic